|

Part 1

Most people think of Asians as recent immigrants to the Americas, but the first Asians--Filipino sailors--settled in the bayous of Louisiana a decade before the Revolutionary War. Asians have been an integral part of American history since that time. COOLIES, SAILORS AND SETTLERS explores how and why people from the Philippines, China and India first arrived on the shores of North and South America, and it portrays their survival amid harsh conditions, their re-migrations, and finally their permanent settlement in the New World. The film travels across oceans and centuries of time to trace the globally interlocking story of East and West--from a village in Guangdong Province and Spanish military barracks in Manila to a Chinese cemetery in Havana and the Peabody Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, where early Asian imports are on display. The first program of ANCESTORS IN THE AMERICAS introduces the "documemoir" approach that characterizes the series. This approach stretches the traditional documentary genre in order to represent an inaccessible past and imagine what life was like for these early voyagers to the West. The dramatic voice and presence of the Asian Everyman narrator represents the Asian perspective throughout the film, capturing the first-person perspective of those who experienced this history. In seeking out his own story, he guides us in examining and interpreting historical records, and his voice conveys a drama and passion often absent in conventional historical narratives.

In looking for the source of Asians in the Americas, the film points to Western expansionism and the self-serving idea that the "white man's burden" was to "save" the barbarian masses of the world. Thus, the West colonized much of Asia as well as the New World, a move vividly illustrated in the film's mapping of these global movements. "Asia was always on the Western mind," observes scholar Gary Okihiro. Both Columbus' nautical quest for Spain and, three centuries later, Lewis and Clark's exploration of the Northwest Passage--on assignment from Thomas Jefferson--were journeys undertaken in search of a direct route to Asia and with it, wealth from global trade in textiles, spices, crafts, porcelains, silk and tea. At the center of early trade with Europe and the New World was the Philippines. As far back as the 17th century, Filipino sailors worked on Spanish galleons which plied trade routes between Spain's two colonies: Manila in the Phillipines and Acapulco in Mexico. Typically a third to half of their crews jumped ship upon hitting port. Some of the Filipinos who left their ships in Mexico ultimately found their way to the bayous of Louisiana, where they settled in the 1760s. The film shows the remains of Filipino shrimping villages in Louisiana, where, eight to ten generations later, their descendants still reside, making them the oldest continuous settlement of Asians in America.

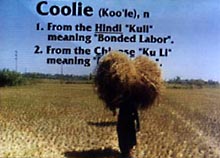

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Western powers, and especially the young American republic, depended upon the "China trade" to build their economic strength. During this period China was considered to be very rich and powerful, while the fledgling American republic was relatively poor and weak. The richest man in the world of that era was the Canton merchant Houqua, who earned his fortune on nothing more than trading in Chinese tea. In a Massachusetts museum we see a vast display of paintings, porcelains, furniture, textile and silver work made by skilled Chinese craftsmen for the world's markets. In the collection made for the U.S. market is the set of china engraved with "J" for Thomas Jefferson. Merchants from America and China enjoyed cordial relations for some time, but these golden years did not last. Of the commercial trade items between China and the West, tea became the most important, as its popularity grew throughout Great Britain and the thirteen colonies. The British imported far more tea than they could export goods to China, creating a trade imbalance. When the trade deficit grew devastatingly large by the 1830s, England, with help from some well-known Americans, began growing and smuggling opium from India—which was under British control—into China, where it was sold to pay for tea. "Great family fortunes were made from the opium trade. Their names read very much like a who's who in America: the Cushings, the Cabot family, Delano, as in Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Perkins, as in the Perkins Hall at Harvard." As Chinese opium addiction grew to catastrophic proportions in the early 19th century, China's government moved to bring the illegal trade to a halt. In the film, we see a broad plaza which leads to the museum where China's struggle against the opium trade is commemorated. After appeals to Queen Victoria yielded nothing, the presiding Imperial Commissioner confiscated and destroyed more than two million pounds of opium found in the western warehouses at Canton. For this, the British went to war, concocting an excuse with which American leaders, including former U.S. President John Quincy Adams, fully concurred. These Opium Wars, begun in the 1840s, resulted in debilitating losses for China. Ports previously banned to foreigners were forced open for trade and Western presence, and Hong Kong and Kowloon were annexed by Britain. The most immediate consequence was China's devastating loss of control over the emigration of Chinese, which resulted in their large-scale shipment as indentured laborers to the Caribbean and South America. After the abolition of the African slave trade in the British empire in the early 1800s, there was a shortage of labor in the New World. South China became the West's favored destination to find replacement laborers to export to their New World colonies. Britain also exported laborers from its own colony, India. More than a quarter million Chinese and half a million Asian Indians were shipped to the New World between the 1840s and 1870s under a "new system of slavery" where Asians replaced African slave labor. We meet Lau Chung Mun in Guangdong Province, China, who tells how his grandfather and two great uncles were "bought and sold like pigs" to work in Cuba. Villagers were lured, kidnapped, tricked with worthless contracts, and loaded onto coolie ships modeled on African slave ships, suffering the same "middle passage". Their bare chests were painted with letters to mark their destinations: "P" for Peru, "C" for Cuba, and "S" for the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii).

Upon arrival in the sugar plantations of Cuba or in the toxic guano pits off the coast of Peru—where they faced brutal exploitation without rights, and worked long hours, lashed and shackled—the lives of the "indentured coolies" differed from that of slaves in name only. It was unlikely that they would ever see their homes again. As awareness of the conditions grew, many new workers resisted. The records tell of frequent mutinies on the ships. The exploitation of coolies became so well known that the Chinese government sent representatives to Cuba to question the coolie workers directly. The China-Cuba Commission Report in 1874 preserves for posterity the testimonies of the workers who bravely gave witness to their inhumane treatment and conditions. "There was no peace....One voyage in every 11 had a mutiny....Bands of us threw ourselves upon them: Release us or we will burn the ship! We have nothing to lose....Thirteen times we succeeded and gained our freedom." - Narrator In Cuba today we also meet descendants of those who stayed and brought generations of countrymen to Cuba. Among the early coolie laborers were those who fought alongside Cuban plantation laborers in the uprisings to achieve liberation from Spain in the late 19th century. We see a Cuban monument to the "Chinos mambises," memorializing the "brave Chinese" who fought in that insurrection and remained to make new lives on the island to which they had been unwillingly brought. We see racially mixed Afro/Spaniard/Chinese Cuban people in the streets of Havana today, and Spanish/Chinese names on the tombstones of the large Chinese cemetery in Havana. Asian Indian coolies, facing similar hardships, were taken from their home areas in coastal Calcutta and Madras and sent to the plantations of other British colonies: Trinidad, Jamaica and British Guiana. We hear the plaintive songs of the departing Asian Indian coolies, and see how the villagers of a fishing town set up clay gods in the sand facing the ocean to beseech protection for those who went to sea. "We survived, took root and made a home."- Narrator Some descendants of these Chinese and Indian workers later re-migrated north to the United States. The film takes us to New York, where numerous Indo-Guyanese have settled, forming a large community in Queens. We also meet Fabiana Chiu, a 4th generation Chinese from Peru, whose ancestors possibly labored in Peru, loading ships with the toxic guano that fertilized the farms of the world. By program's end we have come to understand that the earliest Asians arrived in North America by many routes: via Mexico, South America and the Caribbean, and finally, to California, during the Gold Rush. The film concludes by showing a young Chinese man preparing for the voyage to California's "Gold Mountain" in the mid-1800s. Almost simultaneously with the arrival of coolies in the Caribbean and South America this "Gold Mountain" hopeful will arrive by another route in another part of the Americas. He is full of expectation, believing he will return to those who await him. Unlike the coolies who came before him, he will not lose control of his destiny. He is determined to be a free man. The series continues in Part 2 - CHINESE IN THE FRONTIER WEST: An American Story. home | about cet | about Loni Ding | cet productions resources | mailing list | order | site credits | contact us ancestors | guides | documents | discover ancestors Copyright 1998-2017. Center for Educational Telecommunications, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

|

"Today and for over two hundred years, Asians have been a part of the life of the Americas. How did these many people get here? What was it like for those who came first? What would they tell us, if they could speak?" - Narrator

"Today and for over two hundred years, Asians have been a part of the life of the Americas. How did these many people get here? What was it like for those who came first? What would they tell us, if they could speak?" - Narrator "Asian emigration had as much to do with developments in Europe as it did with developments in the Americas or in Asia. Overseas migration was part of European colonizing efforts in different parts of the world." - Professor Sucheng Chan

"Asian emigration had as much to do with developments in Europe as it did with developments in the Americas or in Asia. Overseas migration was part of European colonizing efforts in different parts of the world." - Professor Sucheng Chan "America may think immigrants always come to get something from America, from the West, and take it away, but really it was very different....Long before Asians immigrated, when East met West, it was the West that came to us."

"America may think immigrants always come to get something from America, from the West, and take it away, but really it was very different....Long before Asians immigrated, when East met West, it was the West that came to us." "We labor 21 hours out of 24 and are beaten....On one occasion I received 200 blows, and though my body was a mass of wounds I was still forced to continue labor.... A single day becomes a year.... And our families know not whether we are alive or dead."

"We labor 21 hours out of 24 and are beaten....On one occasion I received 200 blows, and though my body was a mass of wounds I was still forced to continue labor.... A single day becomes a year.... And our families know not whether we are alive or dead."